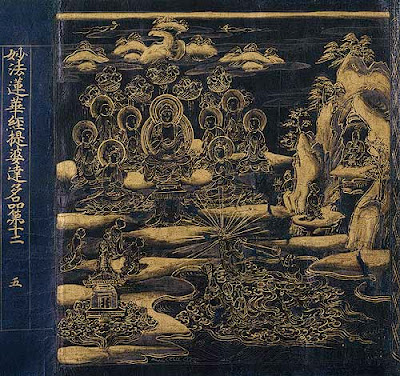

Death of the Historical Buddha (Nehan), Kamakura period (1185–1333), 14th century

Death of the Historical Buddha (Nehan), Kamakura period (1185–1333), 14th century

Unidentified artist

Kyoto, Japan

Hanging scroll; ink, gold, and color on silk 79 x 74 1/4 in. (200.7 x 188.6 cm)

Rogers Fund, 1912 (12.134.10)

In paintings of the Buddha's nirvana, his passing from earthly life to the ultimate goal of an enlightened being, essential tenets of Buddhism are explicit: release from the bonds of existence through negation of desires that cause intrinsic suffering. The large, golden body of Shaka (Shakyamuni) faces west in a final trance after a long life of teaching. Those witnessing the Buddha's passing from earthly life reveal their own imperfect level of understanding in the extent of their grief. Bodhisattvas, who have achieved the spiritual enlightenment of Buddhahood, show a solemn serenity not shared by the lesser beings. Except for the Bodhisattva Jizo, who appears as a monk holding a jewel near the center of the bier, these deities are depicted in princely raiment, with jeweled crowns, flowing scarves, and necklaces covering their golden bodies. Disciples with shaved heads who wear patched robes like the Buddha's weep bitterly, as do the multilimbed Hindu deities and guardians who have been converted to his teaching. Men and women of every class, joined by about thirty animals, grieve in their imperfect understanding of the Buddhist ideal. Even the blossoms of the sala trees change hue. From the upper right, Queen Maya, mother of the dying prince, descends, weeping.

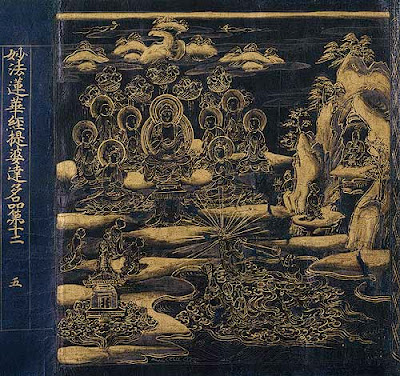

Lotus Sutra, Heian period (794–1185), 12th century

Lotus Sutra, Heian period (794–1185), 12th century

Japan

Gold on indigo-dyed paper 11 3/4 x 339 3/4 in. (29.8 x 863 cm)

Seymour Fund, 1965 (65.216.1)

The Lotus Sutra, promulgated in India around the early part of the third century A.D., is believed to be the final teaching of Shakyamuni at Vulture Peak. It was part of Buddhist worship in Japan as early as the sixth century and became the most popular sutra. The Lotus Sutra emphasizes the ultimate Mahayana belief that Buddha's compassion is open to all, regardless of gender or station in life. In the late Heian period, lavishly produced copies of this text accounted for most of the thousands of such devotional offerings commissioned by the aristocracy to gain religious merit. Following Chinese precedent, they were often painted in gold and silver on paper or silk dyed deep indigo or purple.

This illustration is painted on the frontispiece that precedes the written scripture. It combines depictions of three episodes from chapters 12 to 15 of the Lotus Sutra. Its composition skillfully combines iconic images of the Buddha with narrative vignettes. Here, the daughter of the Dragon King of the Sea offers the radiant jewel to Buddha preaching on Vulture Peak (rendered in the shape of a bird's head). The episode contains the essence of the scripture: the girl's offering is accepted and she is immediately changed into a man, with many features of a bodhisattva, seated on a jeweled lotus. Thus, the compassion of the Buddha offered salvation to women, whose bodies were regarded as unclean and preclusive of attaining enlightenment. Balancing this scene is an illustration of an episode from the Buddha's former life: as a king, Buddha so desired true knowledge that he promised all his wealth and power and lifelong servitude to whoever could reveal it. Here, he is seen twice, once kneeling before the sage who taught him and again bearing firewood in fulfillment of his vow.

Birth of the Buddha, Kushan period

Pakistan (ancient region of Gandhara, probably Takht-i-Bahi)

Stone 6 x 7 in. (16 x 19.7 cm)

Gift of The Kronos Collections, 1987 (1987.417.1)

The Buddha's mother, Maya, delivered him miraculously in a garden in Lumbini, located in present-day southern Nepal. She stood beneath a tree and, with her right arm, clung to a branch for support. This pose mirrors one given to ancient Indian female nature spirits whose touch, it was believed, caused a tree to bloom and fruit. The figure of the Buddha-to-be, although somewhat damaged, can be seen emerging from Maya's side, his head surrounded by a halo. The child was received and bathed by attending gods, who stand to Maya's right. The woman to Maya's left is probably her sister, who raised the Buddha after Maya's death a week after his birth. The attendant on the farthest right holds a pitcher filled with water for the ritual bath.

The Dream of Queen Maya, Kushan period, 1st century a.d.

Pakistan (ancient region of Gandhara, probably Takht-i-Bahi)

Schist 6 1/2 x 7 5/8 in. (16.5 x 19.4 cm)

Gift of Marie-Hélène and Guy Weil, 1976 (1976.402)

This scene depicts the Buddha's miraculous conception. The Buddha's mother, Maya, lies sleeping on her right side. Female attendants surround her, including a guard who stands at the head of her bed holding a large sword. Above her is a circle that once contained an image of the Buddha-to-be in the form of a divine white elephant, descending from a heavenly abode to enter her womb. Maya is dreaming that this is taking place.

This relief comes from an area of ancient Pakistan known as Gandhara, which was reached by Alexander the Great in 329–326 B.C. and later ruled by the Kushans in the first through third centuries. The Kushans had extensive trade contact with Rome and the artistic influence that came with these contacts can be seen in the Mediterranean-inspired robes worn by Maya and her attendants.

The Great Departure and the Temptation of the Buddha, Ikshvaku period, ca. first half of 3rd century

India (Andra Pradesh, Nagarjunakonda)

Limestone 56 3/4 x 36 1/4 x 6 in. (144.2 x 92.1 x 15.2 cm)

Fletcher Fund, 1928 (28.105)

This large limestone panel depicts two scenes from the life of the Buddha. The lower scene shows the moment when Siddhartha, the Buddha-to-be, secretly leaves his father's palace in the middle of the night. Four dwarfs hold up his horse's hooves so that he can depart silently. The upper scene represents the temptation of Siddhartha by Mara's daughters (seen to Siddhartha's right) and the assault by Mara's armies on the night in which he became a buddha.

This panel once clad a large stupa, a hemispherical burial mound that held important relics, at the site of Nagarjunakonda in southeastern India. Patronized by the ruling Ikshvakus, Nagarjunakonda housed both Hindu establishments that were supported by male members of the family and Buddhist ones sustained by their wives and daughters. The animated imagery and the elegantly corpulent bodies are typical of the art of Nagarjunakonda. The spatially intricate scenes from this region were probably inspired by influences from Rome, with which the region had contact via coastal ports.

The Death of the Buddha, Kushan period, 3rd century

Pakistan (ancient region of Gandhara)

Gray schist 26 x 26 in. (66 x 66 cm)

Lent by Florence and Herbert Irving (L.1993.69.4)

This expressive relief depicts the Buddha's death. His recumbent body is shown surrounded by grieving monks and disciples. At the age of eighty, after eating some tainted food, he became very sick and laid down between two trees to die. Images of his death, after which he passed into nirvana (the extinction of desire), symbolize his complete freedom from the endless cycle of rebirth. In addition to small representations such as this one, colossal images commemorating the moment can be found in many countries in which Buddhism is or was practiced, including India, Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, and Japan.

Fasting Siddhartha, Kushan period, ca. 3rd century

Pakistan (ancient region of Gandhara)

Schist 10 15/16 in. (27.8 cm)

Samuel Eilenberg Collection, Purchase, Rogers, Dodge, Harris Brisbane Dick and Fletcher Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1987 (1987.218.5)

After renouncing his luxurious existence in search of an end to the suffering caused by infinite rebirths, Siddhartha went through six years of profound austerity. At one point, he is said to have eaten only a few grains of rice a day. This subject originated with the artists of ancient Gandhara (an area encompassing parts of present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan), who clearly emphasized Siddhartha's emaciated body; his visible ribs and veins are poignant testimony to years of spiritual trials. The theme was common in Gandhara and though it is not found in later Indian Buddhist sculpture, it reappears in Chinese and Japanese art of the Chan/Zen tradition.

Buddha's First Sermon at Sarnath, Kushan Period, ca. 3rd century

Buddha's First Sermon at Sarnath, Kushan Period, ca. 3rd century

Pakistan (ancient region of Gandhara)

Gray schist 11 1/4 x 12 3/4 in. (28.6 x 32.4 cm)

Gift of Daniel Slott, 1980 (1980.527.4)

The Buddha's first sermon took place in a deer park in Sarnath, four miles outside the city of Benares. In art, this setting is symbolized by the two small deer at the base of the Buddha's seat. The Buddha has his right hand on a wheel, which is the symbol of the Buddha's doctrine (dharma). By turning the wheel with his hand, he figuratively sets the doctrine in motion and disseminates Buddhism through the world. The Buddha is surrounded by six figures. The five robed figures with shaved heads represent the five ascetics who originally abandoned Siddhartha when he ended his six years of stringent yogic practice and fasting and accepted a bowl of rice. They became his first audience and then his first disciples. It is unclear who is represented by the bare-chested sixth figure.

Buddha's Descent from the Trayastrimsha Heaven, Ikshvaku period (3rd–4th century), second half of 3rd century

India, Andhra Pradesh, Nagarjunakonda

Limestone 48 x 29 3/4 in. (121.9 x 75.6 cm)

Rogers Fund, 1928 (28.31)

This large limestone panel was originally designed to decorate the lower part of an apsidal stupa from the site of Nagarjunakonda in the southeastern province of Andhra Pradesh. Patronized by the ruling Ikshvakus, Nagarjunakonda houses both Hindu establishments supported by male members of the family and Buddhist ones sustained by their wives and daughters. The detailed imagery of the slab, the somewhat elongated proportions of the people and animals, and the corpulence of the Buddha in the center are typical of the art of Nagarjunakonda.

According to several texts, after his enlightenment, the Buddha Shakyamuni visited the Heaven of the Thirty-three Gods (Trayastrimsha) to preach to his mother—who had passed away without benefit of hearing the doctrine—and the other inhabitants. After living there for three months, he descended to earth at Samkashya. Located in Uttar Pradesh in the north, Samkashya is one of the eight traditional sites of Buddhist pilgrimage. Here, the Buddha is shown flying at the upper right of the panel and preaching to the gods at the upper left. The large central image, shown standing on a lotus, depicts the moment of Shakyamuni's descent at Samkashya. He is attended at his right by a standing figure holding a vajra (thunderbolt scepter) who most likely represents Indra, ruler of the Trayastrimsha Heaven; two women kneeling at the front; and two larger figures placed to the right and left of the central scene.

Model of a stupa (Buddhist shrine), ca. 4th century

Model of a stupa (Buddhist shrine), ca. 4th century

Pakistan, ancient region of Gandhara

Bronze H. 22 3/4 in. (57.8 cm), W. 7 1/2 in. (19.1 cm)

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Donald J. Bruckmann, 1985 (1985.387ab)

Stupas, the earliest Buddhist monuments preserved in India, began as solid hemispherical domes that marked the remains of a great leader or teacher. They were incorporated into early Buddhist art as symbols of the continuing presence of Shakyamuni Buddha after his parinirvana (final transcendence), and as reminders of the path he defined for his followers. Buddhism carried the stupa throughout Asia, where it was interpreted in many forms, including the domed chortens of Tibet and the spired pagodas of China, Korea, and Japan. The square base and ovoid dome derive from monuments built in northwest India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan during the height of Kushan rule, from the late first to the third century. In this somewhat fanciful reliquary, the dome of the stupa is separated from its square base by a lotus pedestal and four rampant griffins. It is further elaborated by four columns—capped by miniature stupas—that encircle the dome, and four somewhat enigmatic columnlike forms on top of the base.

Lunette with Buddha surrounded by adorants, 5th–6th century

Lunette with Buddha surrounded by adorants, 5th–6th century

Hadda, Afghanistan

Stucco H. 16 1/2 in. (42 cm)

Purchase, Walter Burke Gift, and Anonymous Gift, Rogers Fund, and Gift of George D. Pratt, by exchange, 2005 (2005.314)

This lunette, one of only two complete examples known, is a rare survival from the once extensive Buddhist complex at Hadda, which was destroyed in the late 1980s during fighting between the Russians and the Mujahideen. Probably one of a series of lunettes that embellished the high base of a Buddhist stupa, or relic mound, it would have been viewed during ritual circumambulation.

Shakyamuni, the historic Buddha born as Prince Siddhartha, is shown as a bodhisattva wearing the jeweled turban and ornaments of a royal. The elephant and the adjacent bowed figure may refer to an episode from his youth, but his halo, meditating posture, and hierarchic relationship with the surrounding devotees all anticipate his enlightenment—the sculptor's answer to the problem of presenting an icon as an object of veneration and also in the temporal context of a sacred biography. Given that the relief was sculpted in the fifth or sixth century, when classical traditions in the West had become formulaic, the naturalistic anatomy and complex treatment of the interacting devotees seem remarkable. But renewed Western influence would not have been necessary in this period of artistic renaissance, as classical motifs had been part of the Afghan heritage since Alexander the Great's campaign in the fourth century B.C.

Angkor Borei, Cambodia

Stone H. 24 in. (61 cm)

Gift of Doris Wiener, 2005 (2005.512)

This monumental Buddha head is a superb testament to the earliest phase of Buddhism in the lower Mekong Delta. A few heads like this one are all that survive of the large-scale sacred images that must have existed in the region. They give us an indication of the grandeur and spirituality such sculptures must have achieved, as well as a sense of the importance imparted to Buddhist ideology. Typical of Buddha images from the early site of Angkor Borei are the ovoid face, prominent arching eyebrows, outlined eyes and mouth, mouth with upturned corners, and large, close-cropped, snail-shaped curls. With its impressive scale and superb modeling, this head represents the zenith of that great sculptural tradition.

Seated Buddha, Tang dynasty (618–907), early 8th century

Seated Buddha, Tang dynasty (618–907), early 8th century

China

Gilt bronze H. 8 in. (20.3 cm)

Rogers Fund, 1943 (43.24.3)

This striking example of a seated Buddha has the broad shoulders, narrow waist, full and slightly pursed lips, and arched eyebrows characteristic of Chinese Buddhist figures made during the later Tang dynasty. The quality of workmanship, furthermore, suggests that it was probably produced in an urban area, possibly the capital city of Chang'an.

This seated figure performs a graceful variation of the dharmachakra mudra or hand gesture indicating teaching (literally, turning or setting in motion the Wheel [of Buddhist law]). Because Shakyamuni spent more than forty years traveling and lecturing after his enlightenment, this figure could be a representation of the Historical Buddha. He also bears other corporeal markings of enlightened beings: the cranial protuberance (ushnisha) indicating wisdom, elongated earlobes referring to Shakyamuni's royal heritage but without the earrings that he put aside when he chose a spiritual path, and the three neck rings signifying auspiciousness. These physical signs, as well as the flowing monastic robes, derive from Indian prototypes but spread throughout the Buddhist world.

Seated Buddha, 8th–early 9th century

Seated Buddha, 8th–early 9th century

Burma; Pyu kingdom

Bronze H. 7 7/8 in. (20 cm)

Lindemann Fund, 2006 (2006.53)

The Pyu kingdom flourished in central and northern Burma from the early years of the first millennium A.D. to about 832, when Halin, the capital, was sacked by forces of the Nanchao kingdom of southern China. Pyu sculpture is extremely rare. Characteristic of the finest early Southeast Asian sculpture, the fluid modeling of this Buddha image emphasizes soft, flowing volumes rather than linear form. The large ovoid head topped by a wiglike coiffure with a tall, beehive-shaped ushnisha (cranial protuberance) is typical of Pyu bronze Buddhas, as are the full, sensual lips and the long, fleshy nose with a slight hook at the end, perhaps a vestige of Indian influence. (Ritual handling has partially effaced the modeling of the eyes.) The authoritative chest, with its exaggeratedly low pectoral muscles, forms a plane that sweeps down from the broad shoulders to the subtle transition to the soft belly below, where a deep indentation indicates the waist of the Buddha's garment. The thighs are naturalistically proportioned, but the lower legs and feet are somewhat stunted; emphasis is given instead to the large surviving hand, one of the distinguishing characteristics of a Buddha.

This Buddha originally may have held both of his hands in vitarkamudra, the teaching gesture (the small metal tenon that supported his now broken hand can be seen on his right thigh). This two-handed gesture is an iconography that originated with Buddhas produced by the contemporary Mon Dvaravati culture in neighboring Thailand.

Reliquary (?) with scenes from the life of the Buddha, ca. 10th century

Reliquary (?) with scenes from the life of the Buddha, ca. 10th century

India (Jammu and Kashmir, ancient kingdom of Kashmir) or Pakistan

Bone with traces of color and gold paint H. 5 3/8 in. (13.7 cm)

Gift of The Kronos Collections, 1985 (1985.392.1)

Clearly the product of extraordinarily sophisticated and technically skilled workshops, eighth-century carved ivories from Kashmir are rare. Created from an approximately triangular section of bone, believed to be from an elephant, this remarkable piece testifies to the continuation of skills extending the tradition by at least a century. The object, with three scenes depicted on its sides, was probably part of a reliquary. The first two scenes show the miraculous birth of Siddhartha, later to become the Buddha, and his temptation as he meditated at Bodh Gaya immediately prior to becoming the Buddha. The third scene, clearly the focus of the carving, shows a rare representation of a crowned and jeweled Buddha seated cross-legged on a lion throne.

Bookcover with scenes from the life of the Buddha, ca. first half of 10th century

India or Nepal

Ink and color on wood, with metal insets 2 1/2 x 22 3/8 in. (6.4 x 56.8 cm)

Gift of The Kronos Collections and Mr. and Mrs. Peter Findlay, 1979 (1979.511)

Detail: The miracle at Shravasti

This scene is one of four episodes from the life of the Buddha that are painted on the interior surface of a ninth-century cover for a palm-leaf manuscript. It depicts an event that took place in the town of Shravasti, in northeastern India. Here the Buddha was challenged by a group of Brahmanic ascetics who suggested that he could not perform miracles equal to those performed by members of their group. However, the Buddha converted the skeptics by performing a number of miracles, including multiplying his image in all directions, depicted in this representation. He also walked in the air while simultaneously emitting flames from the upper part of his body and waves from the lower part of his body.

Detail: The taming of the elephant Nalagiri

The rogue elephant Nalagiri had been released by Devadatta, Buddha's evil cousin, with the intention that it would kill the Buddha. But as soon as Nalagiri saw Shakyamuni, the elephant became calm and kneeled before him. In this depiction, Ananda, the Buddha's disciple who did not desert him as Nalagiri drew near, stands beside him. This scene is one of four events from the life of the Buddha that were painted on the interior surface of a ninth-century wooden cover for a palm-leaf manuscript. The outer surface of the cover is encrusted with saffron, vermillion, and other organic matter that was ritually applied when the manuscript was in use.

Plaque with scenes from the life of the Buddha, Pala or Pagan period, 12th century

Plaque with scenes from the life of the Buddha, Pala or Pagan period, 12th century

India or Burma

Mudstone 3 15/16 in. (10 cm)

Anonymous Gift, 1982 (1982.233)

The central scene of this devotional plaque depicts Siddhartha's victory over the demon Mara and his subsequent enlightenment. Siddhartha, the Buddha-to-be, sat under a tree in meditation and when it became clear that his enlightenment was near at hand, Mara tried everything in his power to prevent it. He sent his daughters to tempt Siddhartha as well as his armies to disrupt his meditation. The Buddha-to-be responded by touching the earth with his right hand (bhumisparshamudra), a gesture that called the earth goddess to witness his right to achieve enlightenment. She responded positively, Mara and his armies were dispersed, and Siddhartha became the Buddha Shakyamuni.

In Indian art, the Buddha's life was often condensed and codified into a series of eight events. Surrounding the central image on this plaque are depictions of these events (clockwise from lower left): the miraculous birth of the Buddha from the side of his mother Maya; his first sermon at the Deer Park in Sarnath; his taming of the elephant Nalagiri, as indicated by the presence of a kneeling elephant to the right; and at the top, his death. The missing scenes running down the right side would have illustrated his descent from Trayastrimsha Heaven, the miracles he performed at Shravasti, and his acceptance of the monkey's offering of honey. Depicted across the base are the seven jewels of the universal king, flanked on either end by devotees, possibly patrons.

The small size of this plaque suggests that it was a personal devotional object. Many such shrines were found in Burma, and they have been associated with that country until recently. Scholars are now suggesting that many are actually of Indian manufacture, and may have been brought to Burma, by pilgrims who had visited Indian Buddhist sites. A large group of like sculptures has been discovered in Tibet, and were also likely devotional souvenirs.

Buddha sheltered by a naga, Angkor period, 12th century

Buddha sheltered by a naga, Angkor period, 12th century

Cambodia

Bronze 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm)

Gift of Cynthia Hazen Polsky, 1987 (1987.424.19ab)

This sculpture depicts the serpent king Muchilinda protecting the Buddha Shakyamuni from heavy rains. There are numerous extant Cambodian images of this configuration because it was the focus of a cult during the reign of the Cambodian king Jayavarman VII, who ruled the Khmer empire from about 1181 to 1218. Although this scene had been depicted earlier in South and Southeast Asian art, it was the Khmer who popularized it. The reasons that Jayavarman chose to stress the Muchilinda Buddha remain speculative. Snakes were associated with healing, and perhaps because Jayavarman may have been lame, he emphasized healing, as indicated by his construction of hospitals throughout the kingdom.

Death of the Historical Buddha (Nehan), Kamakura period (1185–1333), 14th century

Death of the Historical Buddha (Nehan), Kamakura period (1185–1333), 14th century Lotus Sutra, Heian period (794–1185), 12th century

Lotus Sutra, Heian period (794–1185), 12th century