Lecture on Vesak Day

by Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi

United Nations, 15 May 2000.

Prologue

To begin, I would like to express my pleasure to be here today, on this auspicious occasion of the first international recognition and celebration of Vesak at the United Nations. Though I wear the robe of a Theravada Buddhist monk, I am not an Asian Buddhist but a native of New York City, born and raised in Brooklyn. I knew nothing about Buddhism during the first twenty years of my life. In my early twenties I developed an interest in Buddhism as a meaningful alternative to modern materialism, an interest which grew over the following years. After finishing my graduate studies in Western philosophy, I traveled to Sri Lanka, where I entered the Buddhist monastic order. I have lived in Sri Lanka for most of my adult life, and thus I feel particularly happy to return to my home city to address this august assembly.

Vesak is the day marking the birth, enlightenment, and passing away of the Buddha, which according to traditional accounts all occurred on the full-moon day of May. Ever since the fifth century B.C., the Buddha has been the Light of Asia, a spiritual teacher whose teaching has shed its radiance over an area that once extended from the Kabul Valley in the west to Japan in the east, from Sri Lanka in the south to Siberia in the north. The Buddha's sublime personality has given birth to a whole civilization guided by lofty ethical and humanitarian ideals, to a vibrant spiritual tradition that has ennobled the lives of millions with a vision of man's highest potentials. His graceful figure is the centerpiece of magnificent achievements in all the arts -- in literature, painting, sculpture, and architecture. His gentle, inscrutable smile has blossomed into vast libraries of scriptures and treatises attempting to fathom his profound wisdom. Today, as Buddhism becomes better known all over the globe, it is attracting an ever-expanding circle of followers and has already started to make an impact on Western culture. Hence it is most fitting that the United Nations should reserve one day each year to pay tribute to this man of mighty intellect and boundless heart, whom millions of people in many countries look upon as their master and guide.

The Birth of the Buddha

The first event in the life of the Buddha commemorated by Vesak is his birth. In this part of my talk I want to consider the birth of the Buddha, not in bare historical terms, but through the lens of Buddhist tradition -- an approach that will reveal more clearly what this event means for Buddhists themselves. To view the Buddha's birth through the lens of Buddhist tradition, we must first consider the question, "What is a Buddha?" As is widely known, the word "Buddha" is not a proper name but an honorific title meaning "the Enlightened One" or "the Awakened One." The title is bestowed on the Indian sage Siddhartha Gautama, who lived and taught in northeast India in the fifth century B.C. From the historical point of view, Gautama is the Buddha, the founder of the spiritual tradition known as Buddhism.

However, from the standpoint of classical Buddhist doctrine, the word "Buddha" has a wider significance than the title of one historical figure. The word denotes, not just a single religious teacher who lived in a particular epoch, but a type of person -- an exemplar -- of which there have been many instances in the course of cosmic time. Just as the title "American President" refers not just to Bill Clinton, but to everyone who has ever held the office of the American presidency, so the title "Buddha" is in a sense a "spiritual office," applying to all who have attained the state of Buddhahood. The Buddha Gautama, then, is simply the latest member in the spiritual lineage of Buddhas, which stretches back into the dim recesses of the past and forward into the distant horizons of the future.

To understand this point more clearly requires a short excursion into Buddhist cosmology. The Buddha teaches that the universe is without any discoverable beginning in time: there is no first point, no initial moment of creation. Through beginningless time, world systems arise, evolve, and then disintegrate, followed by new world systems subject to the same law of growth and decline. Each world system consists of numerous planes of existence inhabited by sentient beings similar in most respects to ourselves. Besides the familiar human and animal realms, it contains heavenly planes ranged above our own, realms of celestial bliss, and infernal planes below our own, dark realms of pain and misery. The beings dwelling in these realms pass from life to life in an unbroken process of rebirth called samsara, a word which means "the wandering on." This aimless wandering from birth to birth is driven by our own ignorance and craving, and the particular form any rebirth takes is determined by our karma, our good and bad deeds, our volitional actions of body, speech, and thought. An impersonal moral law governs this process, ensuring that good deeds bring a pleasant rebirth, and bad deeds a painful one.

In all planes of existence life is impermanent, subject to aging, decay, and death. Even life in the heavens, though long and blissful, does not last forever. Every existence eventually comes to an end, to be followed by a rebirth elsewhere. Therefore, when closely examined, all modes of existence within samsara reveal themselves as flawed, stamped with the mark of imperfection. They are unable to offer a stable, secure happiness and peace, and thus cannot deliver a final solution to the problem of suffering.

However, beyond the conditioned spheres of rebirth, there is also a realm or state of perfect bliss and peace, of complete spiritual freedom, a state that can be realized right here and now even in the midst of this imperfect world. This state is called Nirvana (in Pali, Nibbana), the "going out" of the flames of greed, hatred, and delusion. There is also a path, a way of practice, that leads from the suffering of samsara to the bliss of Nirvana; from the round of ignorance, craving, and bondage, to unconditioned peace and freedom.

For long ages this path will be lost to the world, utterly unknown, and thus the way to Nirvana will be inaccessible. From time to time, however, there arises within the world men who, by his own unaided effort and keen intelligence, finds the lost path to deliverance. Having found it, he follows it through and fully comprehends the ultimate truth about the world. Then he returns to humanity and teaches this truth to others, making known once again the path to the highest bliss. The person who exercises this function is a Buddha.

A Buddha is thus not merely an Enlightened One, but is above all an Enlightener, a World Teacher. His function is to rediscover, in an age of spiritual darkness, the lost path to Nirvana, to perfect spiritual freedom, and teach this path to the world at large. Thereby others can follow in his steps and arrive at the same experience of emancipation that he himself achieved. A Buddha is not unique in attaining Nirvana. All those who follow the path to its end realize the same goal. Such people are called arahants, "worthy ones," because they have destroyed all ignorance and craving. The unique role of a Buddha is to rediscover the Dharma, the ultimate principle of truth, and to establish a "dispensation" or spiritual heritage to preserve the teaching for future generations. So long as the teaching is available, those who encounter it and enter the path can arrive at the goal pointed to by the Buddha as the supreme good.

To qualify as a Buddha, a World Teacher, an aspirant must prepare himself over an inconceivably long period of time spanning countless lives. During these past lives, the future Buddha is referred to as a bodhisattva, an aspirant to the full enlightenment of Buddhahood. In each life the bodhisattva must train himself, through altruistic deeds and meditative effort, to acquire the qualities essential to a Buddha. According to the teaching of rebirth, at birth our mind is not a blank slate but brings along all the qualities and tendencies we have fashioned in our previous lives. Thus to become a Buddha requires the fulfillment, to the ultimate degree, of all the moral and spiritual qualities that reach their climax in Buddhahood. These qualities are called påramis or påramitås, transcendent virtues or perfections. Different Buddhist traditions offer slightly different lists of the påramis. In the Theravada tradition they are said to be tenfold: generosity, moral conduct, renunciation, wisdom, energy, patience, truthfulness, determination, loving-kindness, and equanimity. In each existence, life after life through countless cosmic aeons, a bodhisattva must cultivate these sublime virtues in all their manifold aspects.

What motivates the bodhisattva to cultivate the påramis to such extraordinary heights is the compassionate wish to bestow upon the world the teaching that leads to the Deathless, to the perfect peace of Nirvana. This aspiration, nurtured by boundless love and compassion for all living beings caught in the net of suffering, is the force that sustains the bodhisattva in his many lives of striving to perfect the påramis. And it is only when all the påramis have reached the peak of perfection that he is qualified to attain supreme enlightenment as a Buddha. Thus the personality of the Buddha is the culmination of the ten qualities represented by the ten påramis. Like a well-cut gem, his personality exhibits all excellent qualities in perfect balance. In him, these ten qualities have reached their consummation, blended into a harmonious whole.

This explains why the birth of the future Buddha has such a profound and joyful significance for Buddhists. The birth marks not merely the arising of a great sage and ethical preceptor, but the arising of a future World Teacher. Thus at Vesak we celebrate the Buddha as one who has striven through countless past lives to perfect all the sublime virtues that will entitle him to teach the world the path to the highest happiness and peace.

The Quest for Enlightenment

From the heights of classical Buddhology, I will now descend to the plain of human history and briefly review the life of the Buddha up to his attainment of enlightenment. This will allow me to give a short summary of the main points of his teaching, emphasizing those that are especially relevant today.

At the outset I must stress that the Buddha was not born as an Enlightened One. Though he had qualified himself for Buddhahood through his past lives, he first had to undergo a long and painful struggle to find the truth for himself. The future Buddha was born as Siddhartha Gautama in the small Sakyan republic close to the Himalayan foothills, a region that at present lies in southern Nepal. While we do not know the exact dates of his life, many scholars believe he lived from approximately 563 to 483 B.C.; a smaller number place the dates about a century later. Legend holds he was the son of a powerful monarch, but the Sakyan state was actually a tribal republic, and thus his father was probably the chief of the ruling council of elders.

As a royal youth, Prince Siddhartha was raised in luxury. At the age of sixteen he married a beautiful princess named Yasodhara and lived a contented life in the capital, Kapilavastu. Over time, however, the prince became increasingly pensive. What troubled him were the great burning issues we ordinarily take for granted, the questions concerning the purpose and meaning of our lives. Do we live merely for the enjoyment of sense pleasures, the achievement of wealth and status, the exercise of power? Or is there something beyond these, more real and fulfilling? At the age of 29, stirred by deep reflection on the hard realities of life, he decided that the quest for illumination had a higher priority than the promise of power or the call of worldly duty. Thus, while still in the prime of life, he cut off his hair and beard, put on the saffron robe, and entered upon the homeless life of renunciation, seeking a way to release from the round of repeated birth, old age, and death.

The princely ascetic first sought out the most eminent spiritual teachers of his day. He mastered their doctrines and systems of meditation, but soon enough realized that these teachings did not lead to the goal he was seeking. He next adopted the path of extreme asceticism, of self-mortification, which he pursued almost to the door of death. Just then, when his prospects looked bleak, he thought of another path to enlightenment, one that balanced proper care of the body with sustained contemplation and deep investigation. He would later call this path "the middle way" because it avoids the extremes of sensual indulgence and self-mortification.

Having regained his strength by taking nutritious food, one day he approached a lovely spot by the bank of the Nerañjara River, near the town of Gaya. He sat down cross-legged beneath a tree (later called the Bodhi Tree), making a firm resolution that he would never rise up from his seat until he had won his goal. As night descended he entered into deeper and deeper stages of meditation. Then, the records tell us, when his mind was perfectly composed, in the first watch of the night he recollected his past births, even during many cosmic aeons; in the middle watch, he developed the "divine eye" by which he could see beings passing away and taking rebirth in accordance with their karma; and in the last watch, he penetrated the deepest truths of existence, the most basic laws of reality. When dawn broke, the figure sitting beneath the tree was no longer a bodhisattva, a seeker of enlightenment, but a Buddha, a Perfectly Enlightened One, who had stripped away the subtlest veils of ignorance and attained the Deathless in this very life. According to Buddhist tradition, this event occurred in May of his thirty-fifth year, on the Vesak full moon. This is the second great occasion in the Buddha's life that Vesak celebrates: his attainment of enlightenment.

For several weeks the newly enlightened Buddha remained in the vicinity of the Bodhi Tree contemplating from different angles the truth he had discovered. Then, as he gazed out upon the world, his heart was moved by deep compassion for those still mired in ignorance, and he decided to go forth and teach the liberating Dharma. In the months ahead his following grew by leaps and bounds as both ascetics and householders heard the new gospel and went for refuge to the Enlightened One. Each year, even into old age, the Buddha wandered among the villages, towns, and cities of northeast India, patiently teaching all who would lend an ear. He established an order of monks and nuns, the Sangha, to carry on his message. This order still remains alive today, perhaps (along with the Jain order) the world's oldest continuous institution. He also attracted many lay followers who became devout supporters of the Blessed One and the order.

The Buddha's Teaching: Its Aim

To ask why the Buddha's teaching spread so rapidly among all sectors of northeast Indian society is to raise a question that is not of merely historical interest but is also relevant to us today. For we live at a time when Buddhism is exerting a strong appeal upon an increasing number of people, both East and West. I believe the remarkable success of Buddhism, as well as its contemporary appeal, can be understood principally in terms of two factors: one, the aim of the teaching; and the other, its methodology.

As to the aim, the Buddha formulated his teaching in a way that directly addresses the critical problem at the heart of human existence -- the problem of suffering -- and does so without reliance upon the myths and mysteries so typical of religion. He further promises that those who follow his teaching to its end will realize here and now the highest happiness and peace. All other concerns apart from this, such as theological dogmas, metaphysical subtleties, rituals and rules of worship, the Buddha waves aside as irrelevant to the task at hand, the mind's liberation from its bonds and fetters.

This pragmatic thrust of the Dharma is clearly illustrated by the main formula into which the Buddha compressed his program of deliverance, namely, the Four Noble Truths:

(1) the noble truth that life involves suffering

(2) the noble truth that suffering arises from craving

(3) the noble truth that suffering ends with the removal of craving

(4) the noble truth that there is a way to the end of suffering.

The Buddha not only makes suffering and release from suffering the focus of his teaching, but he deals with the problem of suffering in a way that reveals extraordinary psychological insight. He traces suffering to its roots within our minds, first to our craving and clinging, and then a step further back to ignorance, a primordial unawareness of the true nature of things. Since suffering arises from our own minds, the cure must be achieved within our minds, by dispelling our defilements and delusions with insight into reality. The beginning point of the Buddha's teaching is the unenlightened mind, in the grip of its afflictions, cares, and sorrows; the end point is the enlightened mind, blissful, radiant, and free.

To bridge the gap between the beginning and end points of his teaching, the Buddha offers a clear, precise, practicable path made up of eight factors. This of course is the Noble Eightfold Path. The path begins with (1) right view of the basic truths of existence, and (2) right intention to undertake the training. It then proceeds through the three ethical factors of (3) right speech, (4) right action, and (5) right livelihood, to the three factors pertaining to meditation and mental development: (6) right effort, (7) right mindfulness, and (8) right concentration. When all eight factors of the path are brought to maturity, the disciple penetrates with insight the true nature of existence and reaps the fruits of the path: perfect wisdom and unshakable liberation of mind.

The Methodology of the Teaching

The methodological characteristics of the Buddha's teaching follow closely from its aim. One of its most attractive features, closely related to its psychological orientation, is its emphasis on self-reliance. For the Buddha, the key to liberation is mental purity and correct understanding, and thus he rejects the idea that we can gain salvation by leaning on anyone else. The Buddha does not claim any divine status for himself, nor does he profess to be a personal savior. He calls himself, rather, a guide and teacher, who points out the path the disciple must follow.

Since wisdom or insight is the chief instrument of emancipation, the Buddha always asked his disciples to follow him on the basis of their own understanding, not from blind obedience or unquestioning trust. He invites inquirers to investigate his teaching, to examine it in the light of their own reason and intelligence. The Dharma or Teaching is experiential, something to be practiced and seen, not a verbal creed to be merely believed. As one takes up the practice of the path, one experiences a growing sense of joy and peace, which expands and deepens as one advances along its clearly marked steps.

What is most impressive about the original teaching is its crystal clarity. The Dharma is open and lucid, simple but deep. It combines ethical purity with logical rigor, lofty vision with fidelity to the facts of lived experience. Though full penetration of the truth proceeds in stages, the teaching begins with principles that are immediately evident as soon as we use them as guidelines for reflection. Each step, successfully mastered, naturally leads on to deeper levels of understanding, culminating in the realization of the supreme truth, Nirvana.

Because the Buddha deals with the most universal of all human problems, the problem of suffering, he made his teaching a universal message, addressed to all human beings solely by reason of their humanity. He opened the doors of liberation to people of all social classes in ancient Indian society, to brahmins, princes, merchants, and farmers, even humble outcasts. As part of his universalist project, the Buddha also threw open the doors of his teaching to women. It is this universal dimension of the Dharma that enabled it to spread beyond the bounds of India and make Buddhism a world religion.

Some scholars have depicted the Buddha as an otherworldly mystic totally indifferent to the problems of mundane life. However, an unbiased reading of the early Buddhist canon would show that this charge is untenable. The Buddha taught not only a path of contemplation for monks and nuns, but also a code of noble ideals to guide men and women living in the world. In fact, the Buddha's success in the wider Indian religious scene can be partly explained by the new model he provided for his householder disciples, the model of the man or woman of the world who combines a busy life of family and social responsibilities with an unwavering commitment to the values embedded in the Dharma.

The moral code the Buddha prescribed for the laity consists of the Five Precepts, which require abstinence from killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, false speech, and the use of intoxicating substances. The positive side of ethics is represented by the inner qualities of heart corresponding to these rules of restraint: love and compassion for all living beings; honesty in one's dealings with others; faithfulness to one's marital vows; truthful speech; and sobriety of mind. Beyond individual ethics, the Buddha laid down guidelines for parents and children, husbands and wives, employers and workers, intended to promote a society marked by harmony, peace, and good will at all levels. He also explained to kings their duties towards their citizens. These discourses show the Buddha as an astute political thinker who understood well that government and the economy can flourish only when those in power prefer the welfare of the people to their own private interests.

The Parinirvana and Afterwards

The third great event in the Master's life commemorated at Vesak is his parinirvana or passing away. The story of the Buddha's last days is told in vivid and moving detail in the Mahaparinibbana Sutta. After an active ministry of forty-five years, at the age of eighty the Buddha realized his end was at hand. Lying on his deathbed, he refused to appoint a personal successor, but told the monks that after his death the Dharma itself should be their guide. To those overcome by grief he repeated the hard truth that impermanence holds sway over all conditioned things, including the physical body of an Enlightened One. He invited his disciples to question him about the doctrine and the path, and urged them to strive with diligence for the goal. Then, perfectly poised, he calmly passed away into the "Nirvana element with no remainder of conditioned existence."

Three months after the Buddha's death, five hundred of his enlightened disciples held a conference at Rajagaha to collect his teachings and preserve them for posterity. This compilation of texts gave future generations a codified version of the doctrine to rely on for guidance. During the first two centuries after the Buddha's parinirvana, his dispensation slowly continued to spread, though its influence remained confined largely to northeast India. Then in the third century B.C., an event took place that transformed the fortunes of Buddhism and set it on the road to becoming a world religion. After a bloody military campaign that left thousands of people dead, King Asoka, the third emperor of the Mauryan dynasty, avidly turned to Buddhism to ease his pained conscience. He saw in the Dharma the inspiration for a social policy built on righteousness rather than force and oppression, and he proclaimed his new policy in edicts inscribed on rocks and pillars throughout his empire. While following Buddhism in his private life, Asoka did not try to impose his personal faith on others but promoted the shared Indian conception of Dharma as the law of righteousness that brings happiness and harmony in daily life and a good rebirth after death.

Under Asoka's patronage, the monks held a council in the royal capital at which they decided to dispatch Buddhist missions throughout the Indian subcontinent and beyond to the outlying regions. The most fruitful of these, in terms of later Buddhist history, was the mission to Sri Lanka, led by Asoka's own son, the monk Mahinda, who was soon followed by Asoka's daughter, the nun Sanghamitta. This royal pair brought to Sri Lanka the Theravada form of Buddhism, which prevails there even to this day.

Within India itself Buddhism evolved through three major stages, which have become its three main historical forms. The first stage saw the diffusion of the original teaching and the splintering of the monastic order into some eighteen schools divided on minor points of doctrine. Of these, the only school to survive is the Theravada, which early on had sent down roots in Sri Lanka and perhaps elsewhere in Southeast Asia. Here it could thrive in relative insulation from the changes affecting Buddhism on the subcontinent. Today the Theravada, the descendent of early Buddhism, prevails in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos.

Beginning in about the first century B.C., a new form of Buddhism gradually emerged, which its advocates called the Mahayana, the Great Vehicle, in contrast with the earlier schools, which they called the Hinayana or Lesser Vehicle. The Mahayanists elaborated upon the career of the bodhisattva, now held up as the universal Buddhist ideal, and proposed a radical interpretation of wisdom as insight into emptiness, or shunyata, the ultimate nature of all phenomena. The Mahayana scriptures inspired bold systems of philosophy, formulated by such brilliant thinkers as Nagarjuna, Asanga, Vasubandhu, and Dharmakirti. For the common devotees the Mahayana texts spoke of celestial Buddhas and bodhisattvas who could come to the aid of the faithful. In its early phase, during the first six centuries of the Common Era, the Mahayana spread to China, and from there to Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. In these lands Buddhism gave birth to new schools more congenial to the Far Eastern mind than the Indian originals. The best known of these is Zen Buddhism, now widely represented in the West.

In India, perhaps by the eighth century, Buddhism evolved into its third historical form, called the Vajrayana, the Diamond Vehicle, based on esoteric texts called Tantras. Vajrayana Buddhism accepted the doctrinal perspectives of the Mahayana, but supplemented these with magic rituals, mystical symbolism, and intricate yogic practices intended to speed up the way to enlightenment. The Vajrayana spread from northern India to Nepal, Tibet, and other Himalayan lands, and today dominates Tibetan Buddhism.

What is remarkable about the dissemination of Buddhism throughout its long history is its ability to win the allegiance of entire populations solely by peaceful means. Buddhism has always spread by precept and example, never by force. The purpose in propagating the Dharma has not been to make converts, but to show others the way to true happiness and peace. Whenever the peoples of any nation or region adopted Buddhism, it became for them, far more than just a religion, the fountainhead of a complete way of life. It has inspired great works of philosophy, literature, painting, and sculpture comparable to those of any other culture. It has molded social, political, and educational institutions; given guidance to rulers and citizens; shaped the morals, customs, and etiquette that order the lives of its followers. While the particular modalities of Buddhist civilization differ widely, from Sri Lanka to Mongolia to Japan, they are all pervaded by a subtle but unmistakable flavor that makes them distinctly Buddhist.

Throughout the centuries, following the disappearance of Buddhism in India, the adherents of the different schools of Buddhism lived in nearly total isolation from one another, hardly aware of each other's existence. Since the middle of the twentieth century, however, Buddhists of the different traditions have begun to interact and have learnt to recognize their common Buddhist identity. In the West now, for the first time since the decline of Indian Buddhism, followers of the three main Buddhist "vehicles" coexist within the same geographical region. This close affiliation is bound to result in hybrids and perhaps in still new styles of Buddhism distinct from all traditional forms. Buddhism in the West is still too young to permit long-range predictions, but we can be sure the Dharma is here to stay and will interact with Western culture, hopefully for their mutual enrichment.

The Buddha's Message for Today

In this last part of my lecture I wish to discuss, very briefly, the relevance of the Buddha's teachings to our own era, as we stand on the threshold of a new century and a new millennium. What I find particularly interesting to note is that Buddhism can provide helpful insights and practices across a wide spectrum of disciplines -- from philosophy and psychology to medical care and ecology -- without requiring those who use its resources to adopt Buddhism as a full-fledged religion. Here I want to focus only on the implications of Buddhist principles for the formation of public policy.

Despite the tremendous advances humankind has made in science and technology, advances that have dramatically improved living conditions in so many ways, we still find ourselves confronted with global problems that mock our most determined attempts to solve them within established frameworks. These problems include: explosive regional tensions of ethnic and religious character; the continuing spread of nuclear weapons; disregard for human rights; the widening gap between the rich and the poor; international trafficking in drugs, women, and children; the depletion of the earth's natural resources; and the despoliation of the environment. From a Buddhist perspective, what is most striking when we reflect upon these problems as a whole is their essentially symptomatic character. Beneath their outward diversity they appear to be so many manifestations of a common root, of a deep and hidden spiritual malignancy infecting our social organism. This common root might be briefly characterized as a stubborn insistence on placing narrow, short-term self-interests (including the interests of the social or ethnic groups to which we happen to belong) above the long-range good of the broader human community. The multitude of social ills that afflict us cannot be adequately accounted for without bringing into view the powerful human drives that lie behind them. Too often, these drives send us in pursuit of divisive, limited ends even when such pursuits are ultimately self-destructive.

The Buddha's teaching offers us two valuable tools to help us extricate ourselves from this tangle. One is its hardheaded analysis of the psychological springs of human suffering. The other is the precisely articulated path of moral and mental training it holds out as a solution. The Buddha explains that the hidden springs of human suffering, in both the personal and social arenas of our lives, are three mental factors called the unwholesome roots, namely, greed, hatred, and delusion. Traditional Buddhist teaching depicts these unwholesome roots as the causes of personal suffering, but by taking a wider view we can see them as equally the source of social, economic, and political suffering. Through the prevalence of greed the world is being transformed into a global marketplace where people are reduced to the status of consumers, even commodities, and our planet's vital resources are being pillaged without concern for future generations. Through the prevalence of hatred, national and ethnic differences become the breeding ground of suspicion and enmity, exploding in violence and endless cycles of revenge. Delusion bolsters the other two unwholesome roots with false beliefs and political ideologies put forward to justify policies motivated by greed and hatred.

While changes in social structures and policies are surely necessary to counteract the many forms of violence and injustice so widespread in today's world, such changes alone will not be enough to usher in an era of true peace and social stability. Speaking from a Buddhist perspective, I would say that what is needed above all else is a new mode of perception, a universal consciousness that can enable us to regard others as not essentially different from oneself. As difficult as it may be, we must learn to detach ourselves from the insistent voice of self-interest and rise up to a universal perspective from which the welfare of all appears as important as one's own good. That is, we must outgrow the egocentric and ethnocentric attitudes to which we are presently committed, and instead embrace a "worldcentric ethic" which gives priority to the well-being of all.

Such a worldcentric ethic should be molded upon three guidelines, the antidotes to the three unwholesome roots:

(1) We must overcome exploitative greed with global generosity, helpfulness, and cooperation.

(2) We must replace hatred and revenge with a policy of kindness, tolerance, and forgiveness.

(3) We must recognize that our world is an interdependent, interwoven whole such that irresponsible behavior anywhere has potentially harmful repercussions everywhere.

These guidelines, drawn from the Buddha's teaching, can constitute the nucleus of a global ethic to which all the world's great spiritual traditions could easily subscribe.

Underlying the specific content of a global ethic are certain attitudes of heart that we must try to embody both in our personal lives and in social policy. The chiefs of these are loving-kindness and compassion (maitri and karuna). Through loving-kindness we recognize that just as we each wish to live happily and peacefully, so all our fellow beings wish to live happily and peacefully. Through compassion we realize that just as we are each averse to pain and suffering, so all others are averse to pain and suffering. When we have understood this common core of feeling that we share with everyone else, we will treat others with the same kindness and care that we would wish them to treat us. This must apply at a communal level as much as in our personal relations. We must learn to see other communities as essentially similar to our own, entitled to the same benefits as we wish for the group to which we belong.

This call for a worldcentric ethic does not spring from ethical idealism or wishful thinking, but rests upon a solid pragmatic foundation. In the long run, to pursue our narrow self-interest in ever widening circles is to undermine our real long-term interest; for by adopting such an approach we contribute to social disintegration and ecological devastation, thus sawing away the branch on which we sit. To subordinate narrow self-interest to the common good is, in the end, to further our own real good, which depends so much upon social harmony, economic justice, and a sustainable environment.

The Buddha states that of all things in the world, the one with the most powerful influence for both good and bad is the mind. Genuine peace between peoples and nations grows out of peace and good will in the hearts of human beings. Such peace cannot be won merely by material progress, by economic development and technological innovation, but demands moral and mental development. It is only by transforming ourselves that we can transform our world in the direction of peace and amity. This means that for the human race to live together peacefully on this shrinking planet, the inescapable challenge facing us is to understand and master ourselves.

It is here that the Buddha's teaching becomes especially timely, even for those not prepared to embrace the full range of Buddhist religious faith and doctrine. In its diagnosis of the mental defilements as the underlying causes of human suffering, the teaching shows us the hidden roots of our personal and collective problems. By proposing a practical path of moral and mental training, the teaching offers us an effective remedy for tackling the problems of the world in the one place where they are directly accessible to us: in our own minds. As we enter the new millennium, the Buddha's teaching provides us all, regardless of our religious convictions, with the guidelines we need to make our world a more peaceful and congenial place to live.

About the Speaker

Bhikkhu Bodhi was born in New York City in 1944. He received a B.A. in philosophy from Brooklyn College (1966) and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Claremont Graduate School (1972). In late 1972 he went to Sri Lanka, where he was ordained as a Buddhist monk under the late Ven. Balangoda Ananda Maitreya Mahanayaka Thera. Since 1984 he has been editor of the Buddhist Publication Society in Kandy, and since 1988 its president. He is the author, translator, and editor of many books on Theravada Buddhism. The most important of these are The Discourse on the All-Embracing Net of Views (1978), A Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma (1993), The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha (1995), and The Connected Discourses of the Buddha (due for publication in October 2000). He is also a member of the World Academy of Art and Science.

Death of the Historical Buddha (Nehan), Kamakura period (1185–1333), 14th century

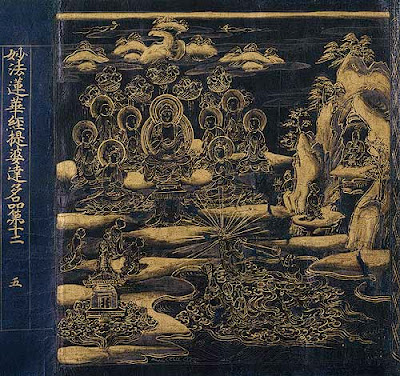

Death of the Historical Buddha (Nehan), Kamakura period (1185–1333), 14th century Lotus Sutra, Heian period (794–1185), 12th century

Lotus Sutra, Heian period (794–1185), 12th century